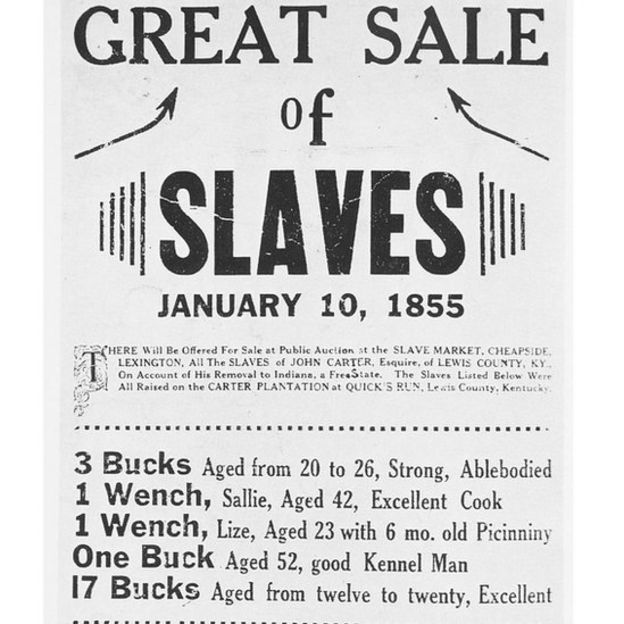

APACHE JUNCTION AZ (IFS) -- The question is, what about the White Slaves? Do they get anything?

Should black Americans get slavery reparations?

API

API

How does a country recover from centuries of slavery and racism? In the US, a growing number of voices are saying the answer is reparations.

Reparations are a restitution for slavery - an apology and repayment to black citizens whose ancestors were forced into the slave trade.

It's a policy notion that many black academics and advocates have long called for, but one that politicians have largely sidestepped or ignored.

But increased activism around racial inequalities and discussions among Democratic 2020 presidential candidates have thrust the issue into the national spotlight.

This week, talk of reparations made headlines after a Fox News contributor argued against the policy by saying the US actually deserves more credit for ending slavery as quickly as it did.

"America came along as the first country to end it within 150 years, and we get no credit for that," Katie Pavlich said on Tuesday, adding that reparations would only "inflame racial tension even more".

The backlash to her comments from liberals and activists was swift.

Bernice King, daughter of Martin Luther King Jr, responded by saying America "doesn't deserve credit for 'ending slavery'" when the ideologies are still prevalent.

What's the history?

Talk of repaying African-Americans has been around since the Civil War era, when centuries of slavery officially ended.

Some experts have calculated the worth of black labour during slavery as anywhere from billions to trillions of dollars. Adding in exploitative low-income work post-slavery pushes those figures even higher.

Even after the technical end of the slave trade, black Americans were denied education, voting rights, and the right to own property - treated in many ways as second-class citizens.

Those arguing for reparations point to these historic inequalities as reasons for current schisms between white and black Americans when it comes to income, housing, healthcare and incarceration rates.

Prof Darrick Hamilton, Executive Director of Ohio State University's Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, says this history is part of America's unique problem.

"From our founding fabric we have based our political and economic institutions on chattel slavery," he told the BBC. "Which makes our institutions not only pernicious but structurally entrenched [in inequalities]."

A brief timeline of slavery in the US

1619 - Some of the first African slaves are purchased in Virginia by English colonists, though slaves had been used by European colonists long before

1788 - The US constitution is ratified; under it, slaves are considered by law to be three-fifths of a person

1808 - President Thomas Jefferson officially ends the African slave trade, but domestic slave trade, particularly in the southern states, begins to grow

1822 - Freed African-Americans found Liberia in West Africa as a new home for freed slaves

1860 - Abraham Lincoln becomes president of the US; the southern states secede and the Civil War begins the following year

1862 - President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation frees all slaves in the seceded states

1865 - The South loses the war; the 13th Amendment to the Constitution formally abolishes slavery

1868 - The 14th Amendment grants freed African Americans citizenship

1870 - The 15th Amendment gives African American men the right to vote; the South begins passing segregation laws

SMITH COLLECTION/GADO

SMITH COLLECTION/GADO

A case for reparations...

In arguing for reparations, Prof Hamilton says the impact of slavery continues to manifest in American society.

"The material consequence is vivid with the racial wealth gap. Psychologically, the consequence is [how] we treat blacks without dignity, that we dehumanise them in public spaces."

From policies excluding primarily black populations - like social security once did - to pushing narratives that blame black Americans for their economic problems, Prof Hamilton says the US has structural problems that must be addressed in order to move forward.

Passing

Before Passing Away, Carol Channing Passed for White

January 24, 2019

By Lisa Page

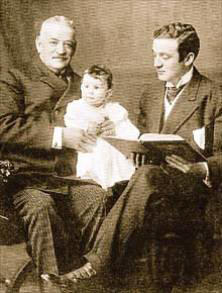

As a kid, I heard that Carol Channing was Black (the word back then was negro). She was one of many celebrities rumored to pass, in Hollywood—a list that included Angie Dickenson, Dinah Shore, and others. These women had large brown eyes, full lips, and bleached blond hair. Looking white—being light-skinned—allowed many Americans to cross the color line into the mainstream, back in a time when that meant serious opportunity. But rumors are rumors.

Then Channing dropped a bomb and published a book where she admitted she had been passing since she was sixteen years old.

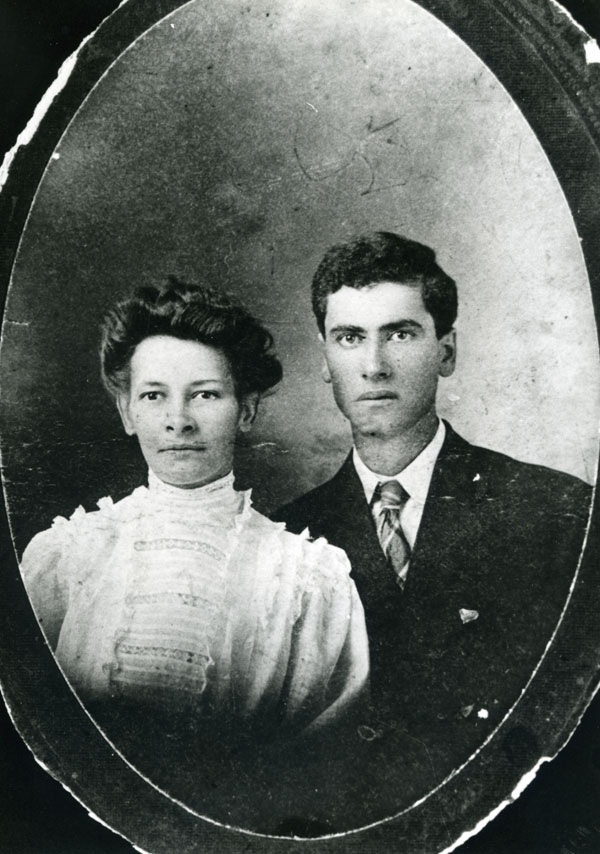

According to her 2002 memoir, Just Lucky I Guess: A Memoir of Sorts, Channing learned of her Black ancestry in 1937. She was on her way to Bennington College, to major in drama and dance, when her mother told her the story.

“I’m only telling you this because the Darwinian law shows that you could easily have a Black baby,” Channing said, quoting her mother. Her father, George Channing, was born in Augusta, Georgia, and his original name was Stucker. Census records from 1890 listed him as ‘colored.’ In a CNN interview with Larry King, Channing said those records were destroyed in a fire and couldn’t be verified. His mother moved him to Rhode Island for a better life.

George Channing became a newspaper editor and Christian Scientist, based in San Francisco who, in photographs, looks white. From all indications, his story rivals Anatole Broyard’s, who famously passed for white at the New York Times for many years. George Channing died in 1957, twenty years after his daughter learned he was Black.

“He wasn’t Black,” Channing exclaimed. “He was this color!” She pinched her own cheeks. JetMagazine described him as a light-skinned man who used two different accents: one for the white world and a different one, at home, where he sang gospel music to his daughter.

When the story broke, Channing was in her eighties. Had she revealed the story earlier, she would never have had the career she had. No Black woman would have been cast as Lorelei Lee in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes in the 1940s, let alone the role of Dolly Levi in Hello, Dolly! She wouldn’t have worn those Bob Mackie dresses on the Great White Way or been the subject of Al Hirschfeld cartoons, or made all those guest appearances on Password and I’ve Got A Secret and What’s My Line. Black celebrities, back then, were marginalized, at best.

But then, weirdly, Channing walked the story back.

“My mother and father had many disagreements,” she told talk show host Wendy Williams in 2010. Her mother may have decided “she would get even” with her father, by inventing the story. I remember how annoyed I was by this news. It was as if Channing chickened out.

“You look light-skinned,” Williams responded. “You have a thicker lip.” Williams went on to call her Soul Sister Number One.

“I don’t know if it’s true, but I hope it’s true,” said Channing. “I can sing and dance better than any white woman anywhere.”

The real passing story, here, is her father’s. Yet Channing is important. She’s the show business metaphor for racial ambiguity. Channing could “sing and dance better than any white woman anywhere” at a time when most of America thought she was white. She’s about our national obsession with the one drop rule.

Americans like stories like hers, because racial and ethnic passing is ubiquitous inside a culture known for self-invention.

But being Black is about more than biology, one drop rule be damned. Being Black is not just about singing and dancing, and shucking and jiving. Being Black goes beyond complexion—it’s a cultural thing. Think of Elizabeth Warren’s recent Indian ancestry revelation, for context. Her DNA backed up her story. But her cultural upbringing was never Native American. Without the culture, it’s just data.

“My grandfather was Nordic German and my grandmother was in the dark,” Channing told Larry King. “I got the greatest genes in show business.” She was always good with the punch line. I admire her for that.

About the Author

Lisa Page is co-editor of We Wear the Mask: 15 True Stories of Passing in America. She teaches at George Washington University where she directs creative writing and is interim director of Africana Studies.

No comments:

Post a Comment