US ranks 28th in Internet connection speed: report

A man surfs the web at an internet cafe.

The United States ranks 28th in the world in average Internet connection speed and is not making significant progress in building a faster network, according to a report released on Tuesday

10Mbps is the new T1 - 7 times T1 speed at the same price with EtherLoop Metro Ethernet - foreThought.net The report by the Communications Workers of America (CWA) said the average download speed in South Korea is 20.4 megabits per second (mbps) -- four times faster than the US average of 5.1 mbps.

Japan trails South Korea with an average of 15.8 mbps followed by Sweden at 12.8 mbps and the Netherlands at 11.0 mbps, the report said. It said tests conducted by speedmatters.org found the average US download speed had improved by only nine-tenths of a megabit per second between 2008 and 2009 -- from 4.2 mbps to 5.1 mbps.

"The US has not made significant improvement in the speeds at which residents connect to the Internet," the report said. "Our nation continues to fall far behind other countries." "People in Japan can upload a high-definition video in 12 minutes, compared to a grueling 2.5 hours at the US average upload speed," the report said. It said 18 percent of those who took a US speed test recorded download speeds that were slower than 768 kilobits per second, which does not even qualify as basic broadband, according to the Federal Communications Commission.

Sixty-four percent connected at up to 10 mbps, 19 percent connected at speeds greater than 10 mbps and two percent exceeded 25 mbps. The United States was ranked 20th in broadband penetration in a survey of 58 countries released earlier this year by Boston-based Strategy Analytics. South Korea, Singapore, the Netherlands, Denmark and Taiwan were the top five countries listed in terms of access to high-speed Internet.

US President Barack Obama has pledged to put broadband in every home and the FCC has embarked on an ambitious project to bring high-speed Internet access to every corner of the United States. According to the CWA report, the fastest download speeds in the United States are in the northeastern parts of the country while the slowest are in states such as Alaska, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. (c) 2009 AFP

SDC BRTI-AMERICA RADIO

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Monday, January 14, 2013

Is Broadband Internet Access a Public Utility?

Is Broadband Internet Access a Public Utility?

By Sam Gustin

Susan Crawford is the author of "Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly in the New Guilded Age.”

Should broadband Internet service be treated as a basic utility in the United States, like electricity, water, and traditional telephone service? That’s the question at the heart of an important and provocative new book by Susan Crawford, a tech policy expert and professor at Cardozo Law School. InCaptive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly in the New Guilded Age, released Tuesday by Yale University Press, Crawford argues that the Internet has replaced traditional phone service as the most essential communications utility in the country, and is now as important as electricity was 100 years ago.

“Truly high-speed wired Internet access is as basic to innovation, economic growth, social communication, and the country’s competitiveness as electricity was a century ago,” Crawford writes, “but a limited number of Americans have access to it, many can’t afford it, and the country has handed control of it over to Comcast and a few other companies.”

Because the U.S. government has allowed a small group of giant, highly profitable companies to dominate the broadband market, Crawford argues, American consumers have fewer choices for broadband service, at higher prices but lower speeds, compared to dozens of other developed countries, including throughout Europe and Asia.

“In Seoul, when you move into an apartment, you have a choice of three or four providers selling you symmetric fiber access for $30 per month, and installation happens in one day,” Crawford told TIME in an interview Tuesday. “That’s unthinkable in the United States. And the idea that the country that invented the Internet can’t get online is beyond my imagination.”

Crawford, who has been a visiting professor at Harvard, Yale and Michigan, spent a year on the National Economic Council as a top telecommunications advisor to President Obama. In her book, she directs much of the blame for the sorry state of the U.S. broadband market at the federal government. “Instead of ensuring that everyone in America can compete in a global economy,” she writes, “instead of narrowing the divide between rich and poor, instead of supporting competitive free markets for American inventions that use information — instead, that is, of ensuring that America will lead the world in the information age — U.S. politicians have chosen to keep Comcast and its fellow giants happy.”

One of the main themes in the book is the “digital divide,” which refers to the fact that millions of people in the U.S., mostly in the poorest and most rural communities, don’t have access to affordable broadband service, including 2.2 million people in New York City, according to Crawford. “We’re depriving people of basic communications access,” she says. Still, broadband and wireless services have become so important to our business and personal lives that most people are willing to pay up, even in the face of high prices driven in part by a lack of competition in the broadband and wireless markets.

Crawford’s top target is Comcast, the nation’s largest cable company, which recently purchased a controlling stake in NBCUniversal, the iconic news and entertainment company. In completing that purchase, which was opposed by media reform advocates and heavily scrutinized by federal regulators, Comcast achieved what might be called the “holy grail” of telecommunications: ownership of a major content creation company, and control of a vast content distribution network.

The FCC‘s approval of the Comcast/NBCU merger created a huge conflict of interest, according to Crawford. “Even as the Internet was becoming the world’s general-purpose network, the merger would put Comcast in a prime position to be the unchallenged provider of everything — all data, all information, all entertainment — flowing over the wires in its market areas,” writes Crawford, who is also an adjunct professor at the School of International Affairs at Columbia University. “Instead of electricity or water, Comcast was gaining dominion over the country’s latest utility infrastructure: high-speed Internet access.”

Let’s take a step back and look at the basic contours of the landline U.S. telecom and cable market. In general, there are three types of wired networks that serve America’s phone, cable, and Internet consumers. Copper wire (traditional phone lines, DSL, slow speeds); cable (faster speeds, mostly for downloading); andfiber (potentially unlimited speeds, data is transmitted through pulses of light). In over 75% of the country, the only broadband choice for Americans will soon be cable, according to Crawford. Consumers are fleeing their relatively slow DSL service so rapidly that 94% of new broadband subscriptions in the third-quarter of 2012 went to faster cable service.

In most of the country — including major cities like Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Detroit, Houston, and Denver — there is only one major cable provider, which happens to be Comcast. In many of these markets, much smaller providers do, in fact, exist around the edges of the dominant company. “Standard Oil did the same thing,” Crawford said during a lecture last fall at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, where she recently joined the board of directors. “You let a little bit of competition exist so you can point to it and say ‘Ha, we’re competing!’ But otherwise it’s mostly controlled by one company.”

Meanwhile, Comcast has sharply reduced its capital expenditures, which have now fallen to 14% of revenues from over 35% a decade ago, even as it enjoys a whopping 95% profit margin on its broadband service. “They’re not expanding and they’re not enhancing their service,” Crawford says. “They’ve done their investment, now they’re just harvesting.” Not surprisingly, Comcast’s stock price increased over 50% in the last year, and nearly 200% over the last four years. “Shareholders are doing well,” Crawford says. “The rest of the country, not so great.”

Verizon’s FIOS high-speed fiber service, which is faster than cable, is available only to about 14% of residences nation-wide, Crawford says, and wireless service “will not substitute” for the lack of fiber access because it is slower. That reality was driven home last year after the FCC allowed Verizon and Comcast to strike a deal to market each other’s services. Verizon will sell Comcast cable service; Comcast will sell Verizon’s wireless service. This is not competition. “Fierce competitors don’t offer to sell each other’s products,” Crawford writes.

Indeed, AT&T and Verizon — which dominate the U.S. wireless market — are moving aggressively to exit their traditional wireline phone businesses, in favor of much more profitable wireless service.

In Europe, where there is much more robust wireless competition, one gigabit service with unlimited minutes and text messages is available for $12 per month, according to Crawford. A comparable service in the U.S. costs anywhere from $50 to $90 per month, depending on the contract. It’s no surprise, then, that the average revenue per user raked in by AT&T and Verizon in the U.S. is soaring, while in Europe the average revenue per user is steadily declining. “People who come here from other countries are just perplexed,” says Crawford. “They wonder what is going on here?”

Given how profitable broadband and wireless service is for the cable and telecom giants, it’s also no surprise that the CEOs of these companies are among the most highly-paid executives in the country. In 2011, Comcast CEO Brian Roberts (whose family controls the voting stock of this ostensibly public company) made $27 million; Verizon CEO Ivan Seidenberg made $26 million; and AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson made $22 million. Seidenberg and Stephenson made about 500 times their employees’ average annual salary, while Roberts and Time Warner Cable CEO Glenn Britt made about 1,000 times what their employees earn every year. (Time Warner Cable is a completely separate public company from TIME parent Time Warner, which spun off the cable giant in 2009.)

For most American companies the ratio is about 380 times, according to Crawford. “I’m not saying we’re doing great on the inequality metric,” she says, “but when it comes to these media companies that would have been viewed as utility companies in the past, it’s really striking.”

According to Crawford, the interests of cable and telecom giants like Comcast, Time Warner Cable, Verizon, and AT&T, are not aligned with the interests of the public. Those corporate giants are concerned first and foremost with maximizing the profits of their shareholders. And all too often, profit maximization — especially in a market that lacks robust competition — is not consistent with providing the best possible service at reasonable prices.

After spending a year as a top tech advisor to President Obama, Crawford concluded that federal policy makers have little incentive to upset the telecom and cable giants. She attributes this partly to the fact that, since 1998, AT&T, Verizon, and the National Cable and Telecommunications industry trade group have spent nearly half a billion dollars lobbying the federal government, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Just in terms of campaign contributions to Congress, AT&T has spent $50 million since 1989, making it the third largest donor during that period of time. And no fewer than 49 members of Congress are actual AT&T shareholders, giving them a direct financial interest in the telecom giants’s profitability.

This has led to what some legal scholars call “regulatory capture” at the Federal Communications Commission, the agency charged with overseeing the industry and preventing abuses that harm consumers. Like many other federal agencies, the FCC has seen numerous examples of the “revolving door“ dynamic in Washington, D.C., in which insiders move back and forth between telecom industry heavyweights and the agencies that are supposed to regulate them. For example, Michael Powell, who served as FCC chairman for four years in the mid-2000s, would later become CEO of the National Cable and Telecommunications industry trade group. He is now the cable and telecom industry’s top D.C. lobbyist.

Meredith Attwell Baker, who was one of the FCC commissioners who approved Comcast’s merger with NBC Universal, left the agency four months later to join Comcast as a highly-paid lobbyist, in a move that infuriated media reform groups. At the time, Craig Aaron, president and CEO of Free Press, a public interest group, described Attwell’s move as “just the latest, though perhaps most blatant, example of a so-called public servant cashing in at a company she is supposed to be regulating. No wonder the public is so nauseated by business as usual in Washington, where the complete capture of government by industry barely raises any eyebrows. The continuously revolving door at the F.C.C. continues to erode any prospects for good public policy.”

Crawford makes a series of policy prescriptions that she says would improve U.S. broadband service, penetration, and competition, while reducing prices. At a minimum, the U.S. government should see to it that each citizen has access to a low-cost (say, $30 per month) Internet connection, says Crawford, much as it does with other basic utilities like electricity and water. Where it’s too expensive for the private sector to provide that service, in very rural areas for example, the federal government should step in.

State and local laws that make it difficult — if not impossible — for new competition to emerge in broadband markets should be reformed, according to Crawford. For example, many states make it very difficult for municipalities to create public wireless networks, thanks to decades of state-level lobbying by the industry giants. In order to help local governments upgrade their communications grids, Crawford is calling for an infrastructure bank to help cities obtain affordable financing to help build high-speed fiber networks for their citizens. Finally, U.S. regulators should apply real oversight to the broadband industry to ensure that these market behemoths abide by open Internet principles and don’t price gouge consumers.

Should broadband Internet service be considered a public utility like water and electricity? “We treated the telephone industry like a utility and people don’t seem to be surprised by that,” says Crawford. “High-speed Internet access plays the same role in American life. It’s just that these guys have succeeded in making us think that it’s a luxury.”

Crawford’s book is the most important volume to be released in the last few years that describes the sad — some might say embarrassing – state of the U.S. telecommunications market. Reasonable people can and do disagree about policy solutions, but the facts are not in dispute. Americans have fewer choices for broadband Internet service than millions of other people in developed countries, yet we pay more for that inferior service. The reason for that, according to Crawford, is that U.S. policy makers have allowed a small number of highly profitable corporate giants to dominate the market, reducing competition and the incentives for these companies to improve service and lower prices.

By taking on one of the most powerful industries in the United States, Crawford knows that she will not endear herself to the CEOs of Comcast, Time Warner Cable, AT&T and Verizon. “I’m not going to be on their Christmas card lists this year,” she quips. And given the entrenched influence of these companies in Washington, D.C., many — if not most — of her policy prescriptions seem a tad far-fetched. Is the U.S. government about to mandate low-cost broadband Internet access for all Americans? It’s not likely any time soon. But her book does provide a vivid and eye-opening description of what ails America’s cable and telecom market, and for that reason, it should be required reading for anyone interested in tech policy. Crawford’s book also lays out a road-map for solutions, quixotic as they may be. But, as Crawford says: “There is always hope.”

Read more: http://business.time.com/2013/01/09/is-broadband-internet-access-a-public-utility/#ixzz2HxlRS3NV

Sunday, January 13, 2013

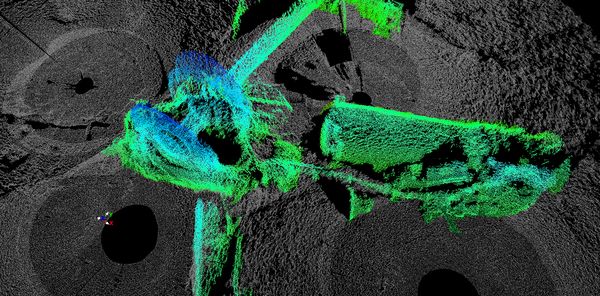

Pictures: Civil War Shipwreck Revealed by Sonar

Time Capsule

Illustration courtesy Becker Collection, Boston College; sonar image courtesy Teledyne BlueView and James Glaeser, Northwest Hydro

New 3-D images (bottom picture) released today by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) show the Civil War-era gunboatU.S.S Hatteras (top) in exquisite detail.

Severe storms, such as 2008's Hurricane Ike, have moved sand off of the shipwreck that sank during a battle exactly 150 years ago, on January 11, 1863.

Resting in 57 feet (17 meters) of water, the shifting sands enabled archaeologists to go in with high-resolution sonars and map newly uncovered parts of the wreck.

The resolution is so good, "it's almost photographic," said archaeologist James Delgado, director of maritime heritage for NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. Delgado and his collaborators have also produced fly-through animations of the historic site and war grave.

"You literally are giving people virtual access to the incredible museum that sits at the bottom of the sea," he said.

—Jane J. Lee

Saturday, January 12, 2013

Fox News Doesn't Understand How Coins Work

Here's Fox News confusing the idea of a coin-shaped pile of platinum

worth $1 trillion and a $1 trillion coin that happens to be made out of

platinum and can be of any size. We saw earlier this week that the

National Republican Campaign Committee also doesn't understand how coins work, so perhaps I can try again to explain.

In my wallet right now I have a bunch of $20 bills, a few $1 bills,

and a $5 bill. These bills are worth different amounts of money due to

the fact that they have different numerals written on them. In terms of

their actual contents, there's very little difference but a $20 bill is

much more valuable than a $1 bill just because. By the same token, if

you write a check for $20,000 it doesn't need to be physically different

from a $200 check except for having different numerals written on it.

Coins are the same. Dimes are more valuable than nickels even though

they're smaller. It is true that several hundred years ago the value of a

coin was driven by its metallic content, but this hasn't been the case

for a long time. The issue doesn't even have anything to do with fiat

money. The point of a gold standard is that you can exchange your

currency for a certain amount of gold. But the currency itself is not made out of gold or anything else in particular. Mostly it's paper. Some of it is coins. But the content of the coins is irrelevant.

If you think about it for a second you'll see that it basically has

to be this way. Quarters and pennies and dimes and nickels all have

different metallic content. Since the relative prices of different

commodities fluctuates on a daily basis, if the value of coins were

based on the value of the metal they contain then the relative value of

different coins would be constantly shifting. You'd have to fire up your

Bloomberg machine every morning to see how much money the coins in your pocket

are worth. That'd be nuts, which is why they write numbers on the

coins. A $1 trillion coin would be a coin of any size with the number "1

Trillion" written on it somewhere near "In God We Trust."Tuesday, January 8, 2013

It’s still the App Store and the Appstore, for now - Or was it "WipeOut" or "Wipe Out"

MEMPHIS TN (IFS) -- It was back in the middle 1960's when the smash hit record "Wipe Out" by the Surfaris went into the court system. Before the record was released to then Dot Records which later became ABC/Dot Records, Merrell Fankhauser received all of the credits from the original producer as the writer of "Wipe Out" as the Impacts released it first, one whole year before the Surfaris version.

As the Court granted the writers to the group "The Surfaris" as the sole writers, because of the spelling of the song. "Wipe Out" verses "WipeOut". As the song was exactly the same in opening, verse, chorus, lyric, etc., the court ordered two difference versions of the song all because of the spelling. Even though, the songs in questioned were recorded by the same group - The Impacts.

It is stated by then president of Del-Fi Records, Bob Keene that he recorded over seventeen different takes of the same song. When the disgruntled record producer picked another version of the production and formed a new group and called them "The Surfaris" and the rest is history. It took over thirty (30) years for Merrell Fankhauser and the Impacts who released the original "WipeOut" one year earlier to get all of the rights to his song. Just a little note about the legal system and names. -KHS

A federal judge dismisses Apple’s false advertising claim against Amazon over the store name.

By Bill Siwicki

Managing Editor, Mobile Commerce, Internet Retailer Magazine

Apple Inc. sells apps for the iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch through an online destination known as the App Store. Amazon.com Inc. sells apps for smartphones and tablets running Google Inc.’s Android operating system, such as Amazon’s Kindle Fire tablet, through an online destination dubbed the Appstore.

Apple was first to name its application store and is suing Amazon, claiming false advertising and trademark infringement.

But the judge presiding over the case has dealt Apple a blow, granting Amazon.com’s motion for summary judgment to dismiss the case’s false advertising claim. U.S. District Judge Phyllis Hamilton wrote in a Wednesday order that Apple did not show how Amazon’s Appstore name confused consumers.

“Apple contends that because its App Store offers so many more apps than Amazon’s Appstore, consumers will be misled into thinking that Amazon’s Appstore will offer just as many,” Judge Hamilton wrote. “There is no evidence that a consumer who accesses the Amazon Appstore would expect that it would be identical to the Apple App Store.”

Hamilton also noted the clear exclusivity of each store, in that the App Store only sells apps for Apple devices and the Appstore only sells apps for Android devices. “Apple has failed to establish that Amazon made any false statement (express or implied) of fact that actually deceived or had the tendency to deceive a substantial segment of its audience,” Hamilton wrote.

Apple and Amazon.comdid not respond to a request for comment. The false advertising claim was just one part of the suit. The case’s trademark infringement claims will be deliberated at trial, which is scheduled to begin in August. "Although I don't think Apple has a good trademark claim, the court's decision isn't a harbinger of its resolution of that claim," says Rebecca Tushnet, a professor at the Georgetown University School of Law.

"It's simply a ruling that, whatever Apple's claims are, they have to be pursued through trademark law." Apple filed the lawsuit, which is being heard in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, in March 2012. It seeks an injunction against Amazon using the words “app” and “store” to describe its application outlet along with profits Amazon has made that are attributable to the name “Appstore.”

As the Court granted the writers to the group "The Surfaris" as the sole writers, because of the spelling of the song. "Wipe Out" verses "WipeOut". As the song was exactly the same in opening, verse, chorus, lyric, etc., the court ordered two difference versions of the song all because of the spelling. Even though, the songs in questioned were recorded by the same group - The Impacts.

It is stated by then president of Del-Fi Records, Bob Keene that he recorded over seventeen different takes of the same song. When the disgruntled record producer picked another version of the production and formed a new group and called them "The Surfaris" and the rest is history. It took over thirty (30) years for Merrell Fankhauser and the Impacts who released the original "WipeOut" one year earlier to get all of the rights to his song. Just a little note about the legal system and names. -KHS

A federal judge dismisses Apple’s false advertising claim against Amazon over the store name.

By Bill Siwicki

Managing Editor, Mobile Commerce, Internet Retailer Magazine

Apple Inc. sells apps for the iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch through an online destination known as the App Store. Amazon.com Inc. sells apps for smartphones and tablets running Google Inc.’s Android operating system, such as Amazon’s Kindle Fire tablet, through an online destination dubbed the Appstore.

Apple was first to name its application store and is suing Amazon, claiming false advertising and trademark infringement.

But the judge presiding over the case has dealt Apple a blow, granting Amazon.com’s motion for summary judgment to dismiss the case’s false advertising claim. U.S. District Judge Phyllis Hamilton wrote in a Wednesday order that Apple did not show how Amazon’s Appstore name confused consumers.

“Apple contends that because its App Store offers so many more apps than Amazon’s Appstore, consumers will be misled into thinking that Amazon’s Appstore will offer just as many,” Judge Hamilton wrote. “There is no evidence that a consumer who accesses the Amazon Appstore would expect that it would be identical to the Apple App Store.”

Hamilton also noted the clear exclusivity of each store, in that the App Store only sells apps for Apple devices and the Appstore only sells apps for Android devices. “Apple has failed to establish that Amazon made any false statement (express or implied) of fact that actually deceived or had the tendency to deceive a substantial segment of its audience,” Hamilton wrote.

Apple and Amazon.comdid not respond to a request for comment. The false advertising claim was just one part of the suit. The case’s trademark infringement claims will be deliberated at trial, which is scheduled to begin in August. "Although I don't think Apple has a good trademark claim, the court's decision isn't a harbinger of its resolution of that claim," says Rebecca Tushnet, a professor at the Georgetown University School of Law.

"It's simply a ruling that, whatever Apple's claims are, they have to be pursued through trademark law." Apple filed the lawsuit, which is being heard in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, in March 2012. It seeks an injunction against Amazon using the words “app” and “store” to describe its application outlet along with profits Amazon has made that are attributable to the name “Appstore.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)