WEST SACRAMENTO CA (IFS) -- President Trump's campaign to drive a wall between the O'odham Nation which crosses two countries. What about them Mr. President? This will never be in the national news, because you will have it suppressed as "Fake News". - KHS

If you are Tohono O’odham and live on the Mexican side, it’s a second-class life

SAN MANUEL, Mexico — Jesús Manuel Casares Figueroa needs a catheter or he will die. His bloated chest pressed against his blue jacket as he sat in a wheelchair in front of his uncle’s modest concrete-block home, one of a handful in this traditional village of the O’odham in the Sonoran desert. His mother touched a gold-colored earring that dangled from Jesús Manuel’s left ear. Her son was born with spina bifida, she explained, and a chronic kidney infection has complicated his condition.

In February, the doctor said Jesús Manuel urgently needed the operation. His family didn’t have the money then, and they don’t have it now.

So in a few hours mother and son will go door to door asking for donations in the neighboring O’odham village, about 60 miles south of Nogales.

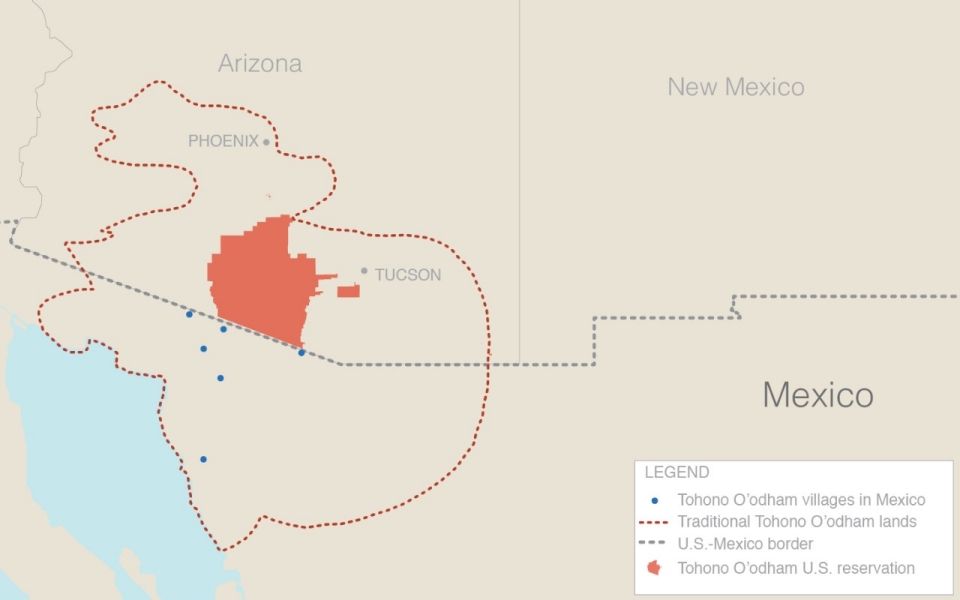

For thousands of years, the Tohono O’odham (meaning “Desert People”) inhabited what is today southern Arizona and the northern state of Sonora in Mexico. But the O’odham were there long before either Mexico or the U.S. existed as nations. “We’ve always been here,” said Amy Juan, 28, a young activist on the reservation. “Nobody can argue that we weren’t here first.”

After the Mexican-American War, the international boundary between the U.S. and Mexico was drawn at the Gila River, just north of the O’odham ancestral lands. But the Gadsden Purchase in 1854 redrew the border right through O’odham territory. The O’odham were never consulted.

“They just drew a line, and when they drew that line O’odham in Arizona became citizens or were considered part of the U.S., O’odham in Mexico of course were not,” said Carlos G. Veléz-Ibáñez, director of the School of Transborder Studies at Arizona State University. “Unlike some of our Canadian borders, you don’t have the opportunity of dual citizenship or being able to determine which country you’re a citizen of.”

In the aftermath of 9/11, O’odham living on the U.S. reservation were forced to deal with the unintended consequences of a militarized border: Border Patrol agents harass and treat them as undocumented migrants on their sovereign land. Their desert landscape and wildlife get clobbered by migrants, traffickers and federal law enforcement. They return home to find cars stolen, houses ransacked by desperate migrants — migrants who far too often don’t survive the desert elements. It’s also not uncommon for tribal members to be lured by fast cash into working as coyotes or mules for the Mexican cartels, ending up in jail themselves.

But less attention is paid to the grave impact the same border has on O’odham in Mexico, who’ve become second-class citizens within their own tribe.

A nation divided

The Tohono O’odham Nation (pronounced TOHN-oh AUTH-um) is a sovereign government and federally recognized Indian nation that claims 25,000 members. Their reservation — established in 1917 — is the second largest in the U.S. and spans 2.8 million acres, about the size of Connecticut. The southern boundary includes 75 miles of the U.S.-Mexico international border.

Estimates vary on how many Tohono O’odham live in Mexico, and the tribal government refused to comment on the topic. The Tohono O’odham Community College website states that about 1,800 enrolled Tohono O’odham reside in Mexico. According to the 2000 national census and subsequent report by Mexico’s National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples, 363 O’odham were living in Sonora, Mexico. However, that tally included only families in which someone in the household spoke the O’odham language, ñiok, which has been almost entirely replaced by Spanish.

When the Tohono O’odham reservation was created, said Veléz-Ibáñez, it was a distinctive land base that O’odham had control over even though it was held in trust by the U.S. government.

“In Mexico that didn’t happen at all. In Mexico they were at the mercy of the Mexican government,” he said. O’odham in Mexico had no special rights or recognition, and throughout the 20th century Mexican ranchers encroached on their land. (It wasn’t until after the Zapatista movement sprang out of the forests in Chiapas in 1996 that Mexico’s federal government officially recognized parcels of indigenous lands.)

Veléz-Ibáñez said the special relationship between the U.S. and native people beginning early on provided O’odham in the U.S. opportunities for education, economic development, housing subsidies, work and training programs — and health care — not available to O’odham in Mexico.

“The Indian health service is not a Cadillac program,” he explained, “but it’s still much better than what O’odham in Mexico had.”

When the border fence was erected — to this day just concrete vehicle barriers connected by chicken wire — it didn’t stop O’odham from crossing between the countries.

“The border meant not a thing to me,” said Henry Jose, a Navy veteran whose story was included in “It Is Not Our Fault,” a collection of testimonies from O’odham on both sides of the border used to make a case to Congress for citizenship for all O’odham. (The book was published in 2001, shortly before 9/11 changed the immigration debate drastically.) “The border is between the white people and the Mexicans but not us O’odham. These are Indian lands, O’odham lands.”

“We used to go back and forth freely,” confirmed Jose Garcia, lieutenant governor of the Sonoran O’odham who serves as a liaison between their traditional leaders and the Tohono O’odham Nation. These days Garcia, 72, splits his time between Arizona, where he owns La Indita restaurant in downtown Tucson, and Magdalena de Kino in Sonora, Mexico, where he advocates for the Mexican O’odham. Garcia’s grandparents were born on the U.S. side and migrated to Mexico. “So I look at Sonora and I look at the Nation as one for me,” Garcia said.

However, especially after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Customs and Border Protection — and the Department of Homeland Security it operates under — saw it much differently.

A border strategy

The Southwest Border Strategy, which was implemented beginning in the early 1990s, was a “prevention through deterrence” approach to illegal immigration. The goal was to crack down on the flow of migrants (and drugs) at popular urban crossing areas like Tijuana–San Diego and Juarez–El Paso, and thereby funnel the illicit traffic to the remote, rugged desert, where temperatures reach 110 degrees in summer. Border Patrol believed the maneuver would give it a tactical advantage, and at the same time “make it so difficult and so costly to enter this country illegally that fewer individuals try.”

However, they underestimated the resolve — and desperation — of migrants in search of economic opportunities. Despite the number of border agents in the Tucson sector skyrocketing from 280 to 1,770 between 1993 and 2004, Tohono O’odham tribal officials estimated that up to 1,500 undocumented migrants per day were crossing through the reservation.

For the O’odham, crossing the border anywhere but official points became illegal. Garcia says the fortified border further isolated the Sonoran O’odham.

“In Mexico the government has this mindset that the O’odham people that are living along the border are more Americans than Mexican citizens,'' he said. "And O’odham on this side have that same mind concept — that they’re in Mexico, so let Mexico take care of them. So we’re caught between a rock and a hard place.”

All members of the Tohono O’odham tribe, whether U.S. or Mexican citizens, are entitled to access the reservation clinic overseen by the U.S. government. In practice, border policies prevent this.

According to the Tohono O’odham Nation’s Resolution 98-063, passed in 1998, “enforcement of U.S. immigration laws has made it extremely difficult for all Tohono O’odham to continue their sovereign right to pass and re-pass the United States-Mexico border as we have done for centuries as our members are routinely stopped by the U.S. Border Patrol, while others have been actually ‘returned’ to Mexico even though enrolled.”

Many O’odham in Mexico do not have the proper documentation now required to cross legally, whether birth certificates (lacking due to home births) or tribal IDs (because they lack the paperwork or witnesses required for enrollment).

Plus, with the Sonoran desert being used as a backyard for criminal organizations, O’odham families in the U.S. have largely halted visits to their Mexican O’odham kin.

The fear is not unfounded.

“In my village [Wo’osan] you can’t even go out to the wooded area because you would never know who’s there,” said Garcia. Other areas of O’odham villages have been abandoned, he added, and turned into campsites by criminal organizations.

The problem of representation

But for Garcia, the issue facing O’odham in Mexico is not just access to resources but representation. “There isn’t any representation in the [tribal] council that comes from Sonora,” he said.

Even among those O’odham in Mexico who are officially enrolled in the Nation, very few are registered to one of the 12 districts on the reservation. Most Sonoran O’odham IDs state N.D., no district, Garcia said. This means that even though the tribe includes its Mexican members in the annual count that determines federal funds, those funds get divvied up between the districts and don’t reach the O’odham in Mexico.

If the tribe would allow it, he said, representation would give O’odham in Mexico a say in the tribal government.

“They would have a voice in representing the housing needs, the road needs, the education, the health issue — all those things would be voiced here on the Nation if we had representation.”

Garcia believes it’s vital to the economic improvement of O’odham in Mexico as well as their ability to keep their culture and identity intact.

“If the O’odham in Mexico don’t get organized, if they don’t get a unity going, they’re always going to be in the same boat,” he said.

Facing extinction

David Ortega agrees. The self-described warrior with long salt-and-pepper hair was born in the U.S. but moved to Mexico where he lives with his wife, Patty. “We have lost that oneness,” he said. “We as native people have always supported each other. We’ve always lived together as one throughout history and culture.”

“I feel we have to unify first, bring ourselves back from the dominant culture’s way, relearn what we are as O’odham people.”

To that end, he’s spent the last year traveling from village to village in Sonora, Mexico, teaching O’odham language classes so that O’odham in Mexico don’t completely lose touch with their traditions and "him dag,'' or way of life.

But it’s a race against time.

Just a few generations go, almost every O’odham, whether in the U.S. or Mexico, spoke O’odham.

In 2012, researchers from the Center of Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS) classified 143 indigenous languages in Mexico that are facing extinction. The O’odham language (still called Pápago in Mexico) falls into the most vulnerable, or “critically endangered,” group, with only 116 speakers. Jacob Franco Hernández, a Ph.D. student at the University of Sonora, says even this count is not accurate. Since 2008 he’s worked with the Sonoran O’odham, and in his 2010 master’s thesis determined there are only 24 fluent speakers in Mexico.

While O’odham on both sides of the border have adopted the dominant language (whether English or Spanish), those on the U.S. side have maintained a much stronger grip on their indigenous language, history and traditions.

“There are O’odham descendants [in Mexico] that say, ‘We know we’re O’odham, but we don’t have anyone to show us what it is to be O’odham,’” said Garcia, the former lieutenant governor. “And most of our elders in Mexico that did know something about ‘him dag’ are gone. They say there’s a lot of elders still there, but what I see is a lot of elders who don’t have any interest in teaching. And we’re trying to revive and restore some of the traditional things that have been forgotten in Mexico.”

A blessing in song

Outside Jesús Manuel’s uncle’s home, eight family members gathered under a tree adorned with rusting horseshoes and other metal tools and trinkets. After a hearty breakfast of tortillas, beans, and fresh chicharrones cooked over an outdoor fire, a handful of O’odham youth from the reservation said goodbye to Jesús Manuel’s family.

Alex Soto, of the hip-hop duo Shining Soul shared a rap from his new album critiquing U.S. immigration policy.

Amy Juan wanted to leave the family with a traditional song. In the O’odham culture, songs are also prayers. She chose a song in ñiok that’s been passed down through the generations and was taught to her by a now-deceased elder. (To see a photo of Juan and to listen to her sing, see below.) It’s about a young man’s journey to the ocean. On the shore he dances the i:dahiwan, the cleansing dance, asking for blessings for everyone.

“I wanted to leave the family with something that would connect them to their O’odham roots,” Juan said. “I left it not only with the family but with the land, to remind it and them of our presence and to remind them that it is still O’odham land and our ancestors still remain there.”

Listen: A Traditional Tohono O’odham Song

Listen: A Traditional Tohono O’odham SongIntroductory Information

The Tohono O’odham Nation is comparable in size to the state of Connecticut. Its four non-contiguous segments total more than 2.8 million acres at an elevation of 2,674 feet. Within its land the Nation has established an Industrial Park that is located near Tucson. Tenants of the Industrial Park include Caterpillar, the maker of heavy equipment; the Desert Diamond Casino, an enterprise of the Nation; and, an 23 acre foreign trade zone.

The lands of the Nation are located within the Sonoran Desert in south central Arizona. The largest community, Sells, functions as the Nation’s capital.

Of the four lands bases, the largest contains more than 2.7 million acres. Boundaries begin south of Casa Grande and encompass parts of Pinal and Pima Counties before continuing south into Mexico.

San Xavier is the second largest land base, and contains 71,095 acres just south of the City of Tucson. The smaller parcels include the 10,409-acre San Lucy District, located near the city of Gila Bend, and the 20-acre Florence Village, which is located near the city of Florence.

The landscape is consistently compelling: a wide desert valley, interspersed with plains and marked by mountains that rise abruptly to nearly 8,000 feet.

As of December, 2000, the population was reported at nearly 24,000 people.

Government And Council Members Listing

Edward D. Manuel, Chairman

Verlon M. Jose, Vice Chairman

Legislative Council

Timothy Joaquin, Legislative Chairman

Edward Manuel, Legislative Vice-Chairman

Frances Miguel, Baboquivari

Frances Antone, Baboquivari (Alternate)

Ethel Garcia, Chukut Kuk

Billman Lopez, Chukut Kuk (Alternate)

Timothy Joaquin, Gu Achi

Cynthia Manuel, Gu Achi (Alternate)

Pamela Anghill, Gu Vo

Grace Manuel, Gu Vo (Alternate)

Sandra Ortega, Hickiwan

Louis Lopez, Hickiwan (Alternate)

Chester Antone, Pisinemo (Alternate)

Lorraine Eller, San Lucy

Jana Montana, San Lucy (Alternate)

Olivia Villegas-Liston, San Xavier

Hilarion Campus, San Xavier (Alternate)

Frances Conde, Schuk Toak

Frederick Jose, Schuk Toak (Alternate)

Evelyn Juan-Manuel, Sells

Arthur Wilson, Sells (Alternate)

Nicholas Jose, Sif Oidak

Mary Lopez, Sif Oidak (Alternate)

District Chairpersons

Baboquivari District – Chairman Veronica J. Harvey

Chukut Kuk District - Chairwoman Marla Kay Henry

Gu Achi District – Chairman Camillus Lopez

Gu Vo District – Chairwoman Geneva S. Ramon

Hickiwan District – Chairwoman Delma Garcia

Pisinemo District – Chairman Stanley Cruz

San Lucy District – Chairman Albert Manuel Jr.

San Xavier District – Chairman Austin Nunez

Schuk Toak District – Chairwoman Phyllis Juan

Sells District – Chairman, Vacant

Sif Oidak District – Chairwoman Rita A. Wilson

Public Relations

Attractions

The San Xavier district is known for the San Xavier Mission Del Bac, the White Dove of the Desert. In addition to this magnificent mission, the area maintains an Indian arts and crafts market. Nearby Baboquivari Mountain Park has picnic facilities.

Gaming

Gaming was authorized August 11, 1993 and on October 12 of that year, the Desert Diamond Casino opened. The casino offered visitors a choice of 500 slot machines which has resulted in the Nation being the 13th largest employer in the area, representing over 2,400 jobs.

In 1995 the facility was expanded to include bingo and live card dealers as well as 500 slot machines. A second, smaller casino, Golden Hasan opened 1999, and has 100 slot machines.

The Desert Diamond Casino, open 24 hours, and is located at 7350 South Old Nogales Highway in Tucson, Arizona.

Visitor Amenities

Basic community services are available on the “main”, Gila Bend and San Xavier reservations.

San Xavier Development Authority (520)741-1940

Baboquivari Mountain Park (520)383-2236

Special Tribal Events

February (1st weekend) – Annual Rodeo

Contact

Tohono O’Odham Nation

PO Box 837

Sells, AZ 85634

Phone: (520) 383-2028

Fax: (520) 383-3379